Last updated on May 3rd, 2022 , 04:49 am

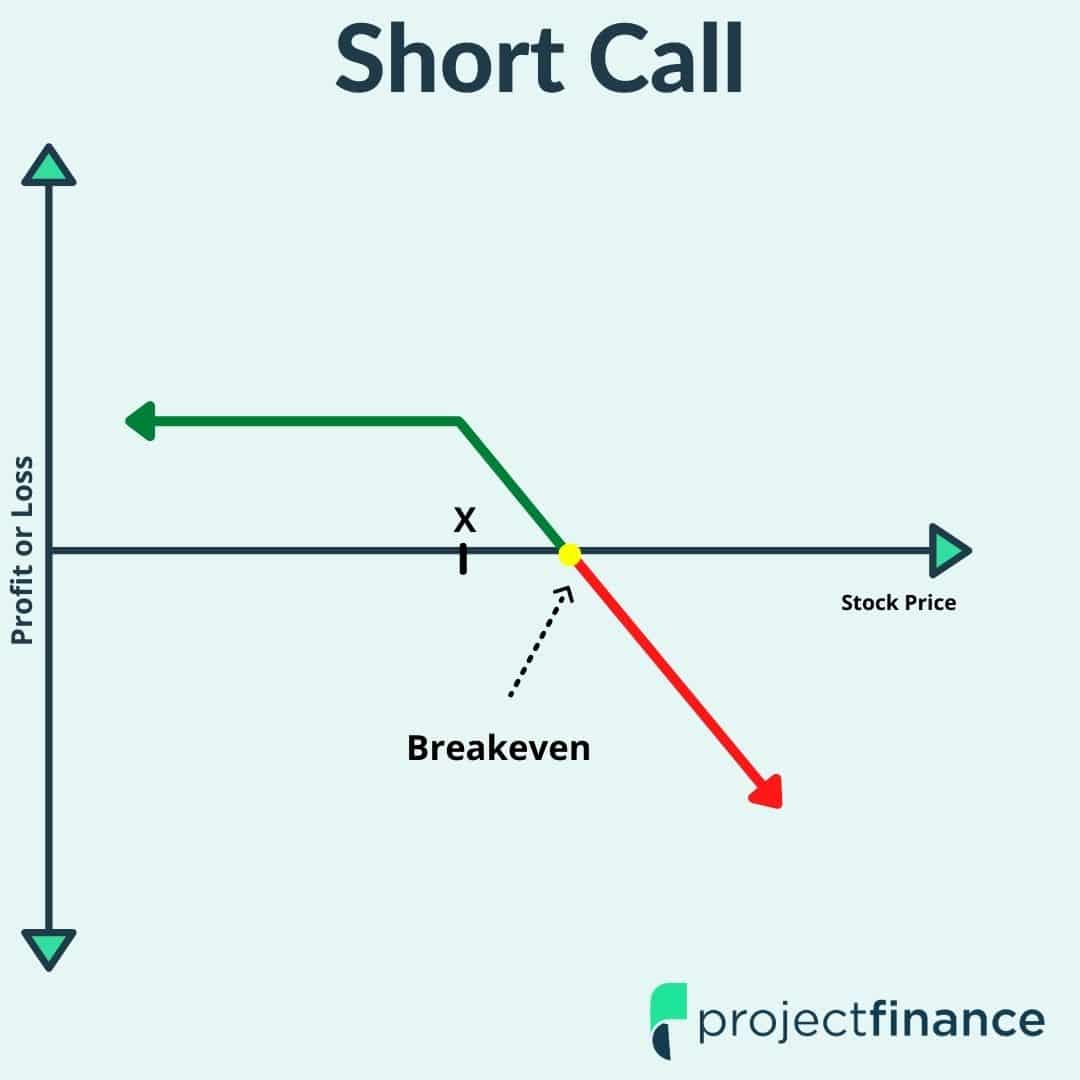

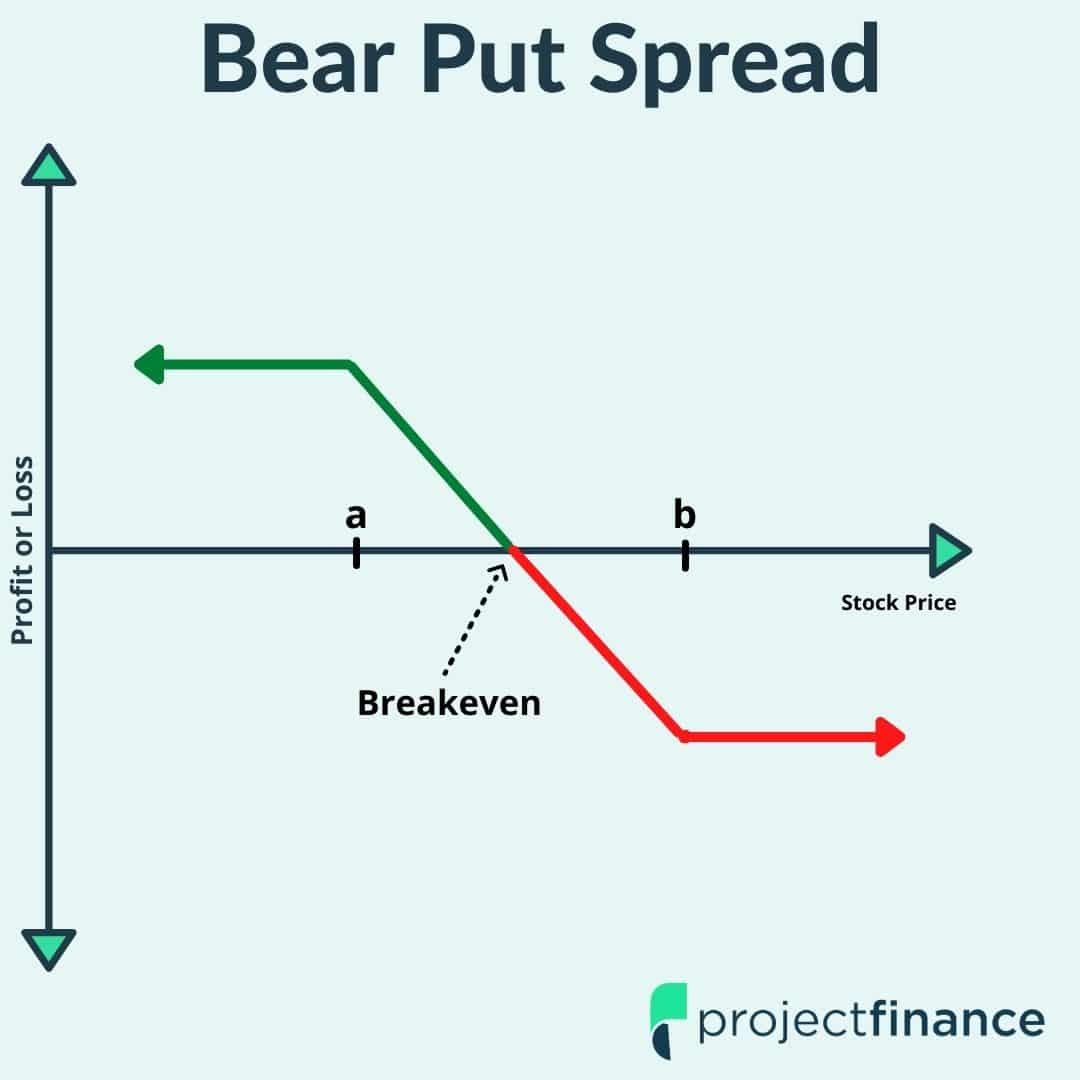

The short iron condor options strategy is a limited risk strategy consisting of simultaneously selling an out-of-the-money call spread and out-of-the-money put spread in the same expiration date cycle.

Since the sale of a call spread is a bearish strategy and selling a put spread is a bullish strategy, combining the two into a short iron condor results in a directionally neutral position. However, if the stock price moves significantly in either direction, the trade will lose money and also become directional.

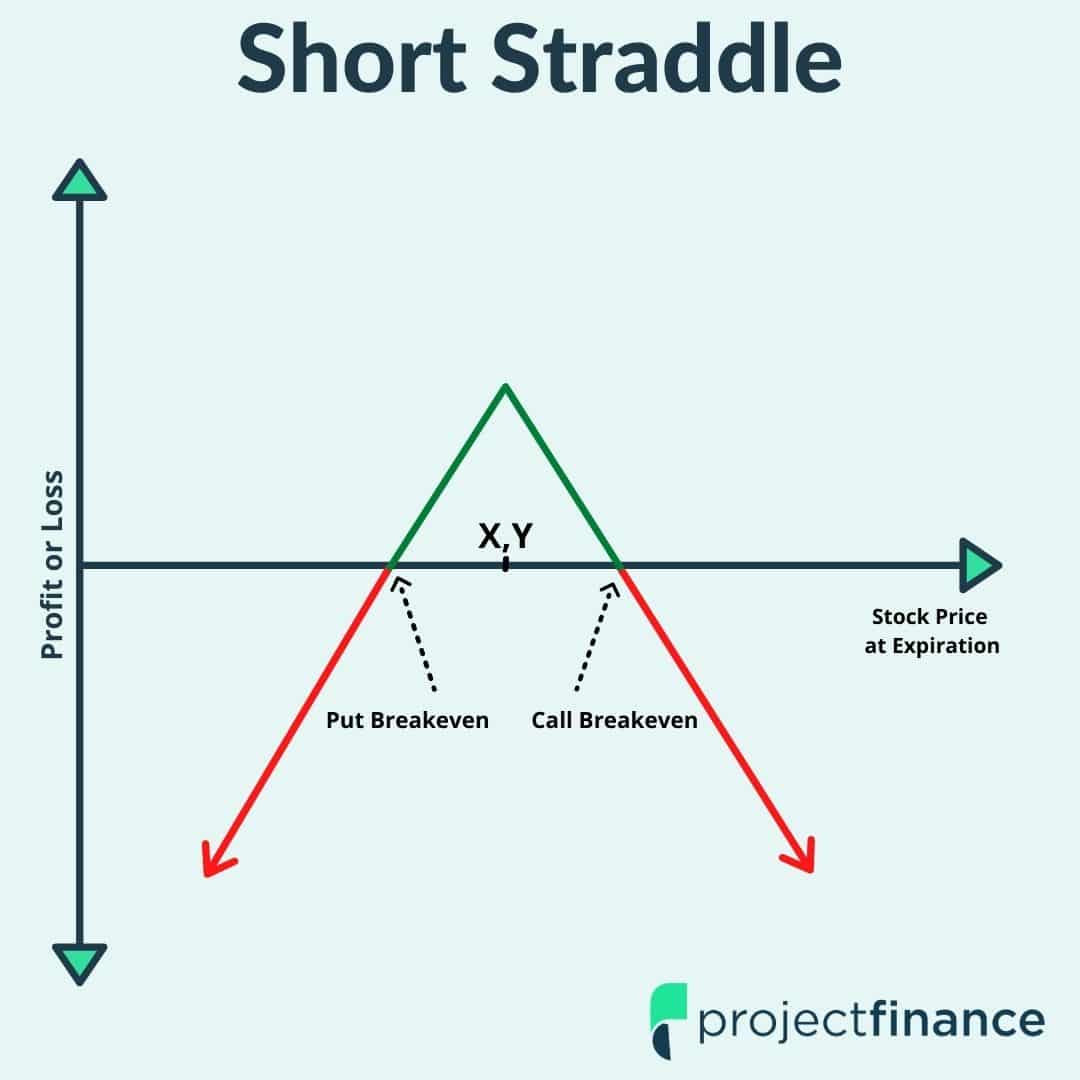

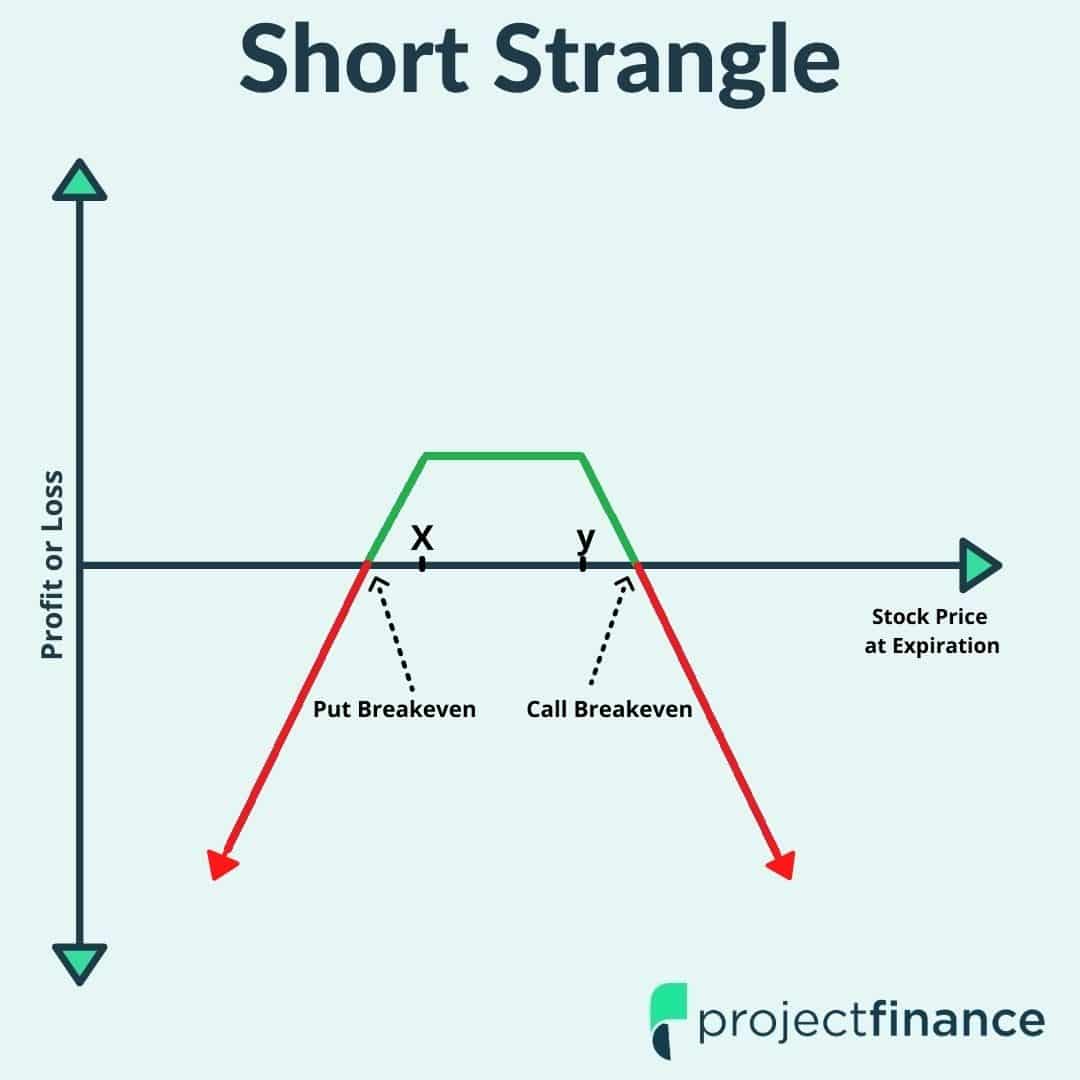

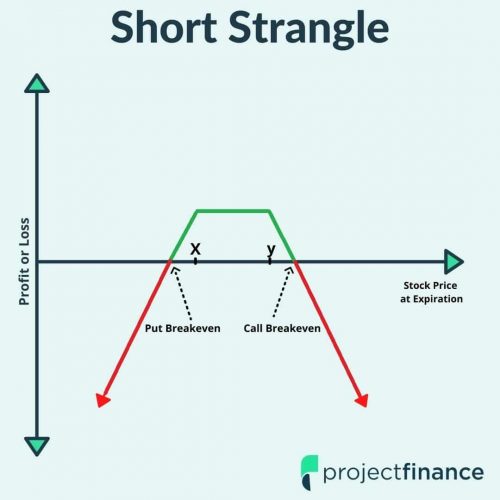

The iron condor strategy is very similar to the strangle, except an iron condor has less risk due to using spreads as opposed to naked short options. When selling iron condors, profits come from the passage of time or decreases in implied volatility, as long as the stock price remains between the two breakeven prices of the position.

Care to watch the video instead? Check it out below!

TAKEAWAYS

- An iron condor consists of selling a put spread (long put/short put) and a call spread (long call/short call) at the same time.

- Both of these spreads must be of the same width and expiration.

- Iron condor’s profit when the options sold fall in value.

- Short iron condors are best suited for market-neutral traders.

- Maximum loss is greater than maximum profit for most iron condors.

- High volatility allows traders to collect greater premium from iron condors sold.

Iron Condor Advantages

Short Iron Condor Strategy Characteristics

➥ Max Profit Potential: Net Credit Received x 100

➥ Max Loss Potential: (Strike Width of Widest Spread – Net Credit Received) x 100

➥ Expiration Breakevens:

1. Upper Breakeven = Short Call Strike Price + Net Credit Received

2. Lower Breakeven = Short Put Strike Price – Net Credit Received

➥Estimated Probability of Profit:

Between 50-99% depending on the strikes chosen. The further the short strikes are from the stock price, the higher the probability of profit. However, higher probability of profit comes at the cost of less potential reward.

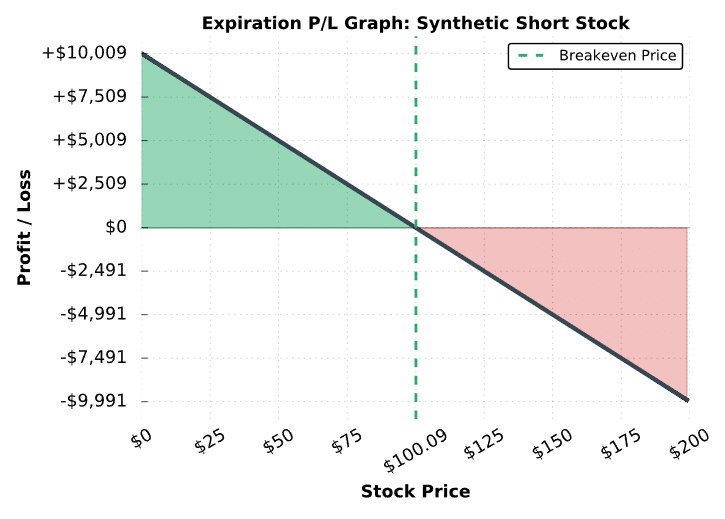

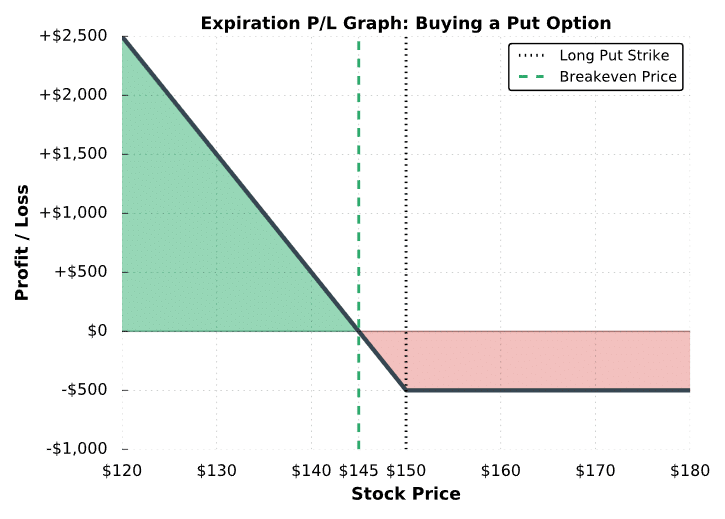

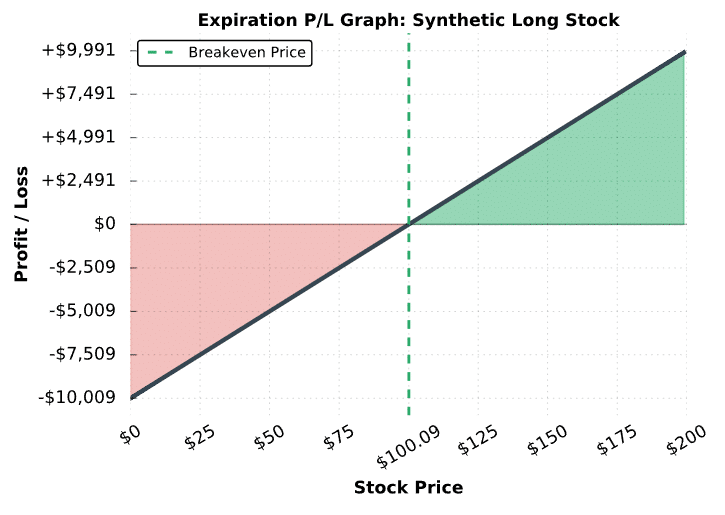

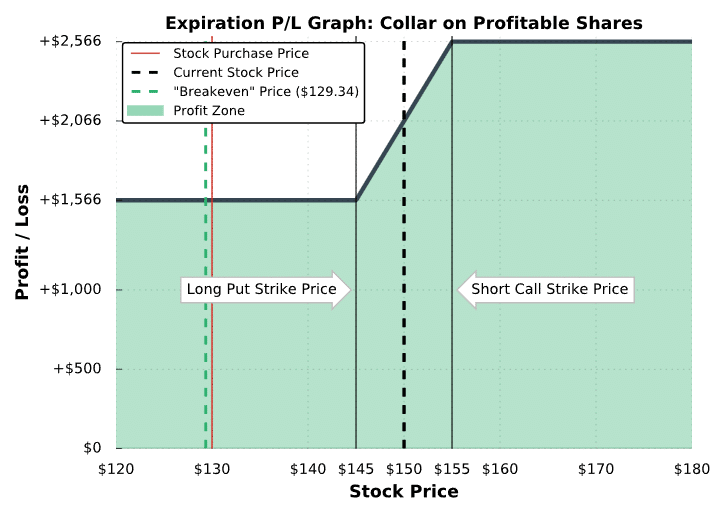

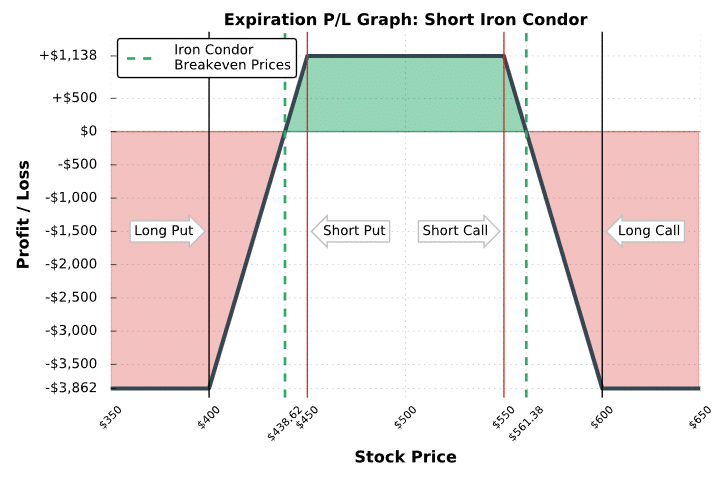

To demonstrate these characteristics in action, let’s take a look at a hypothetical example to visualize the iron condor strategy’s potential profits and losses at expiration.

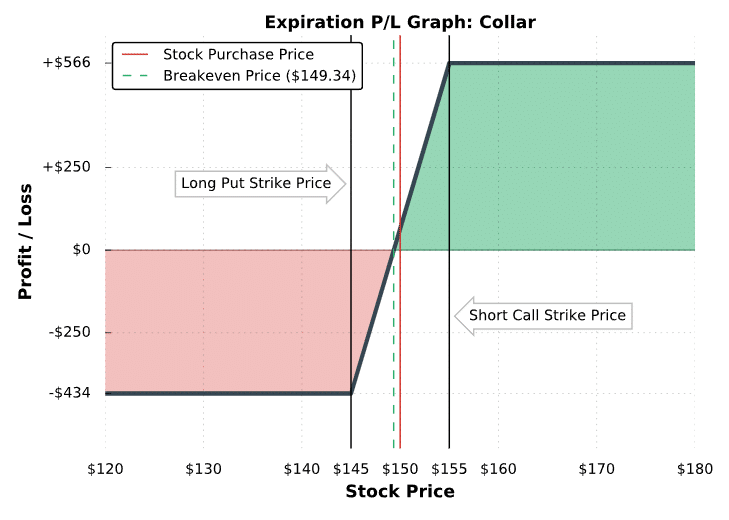

P/L Potential at Expiration

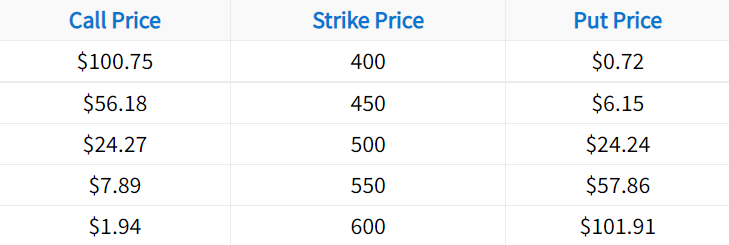

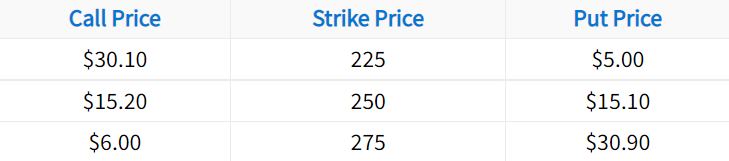

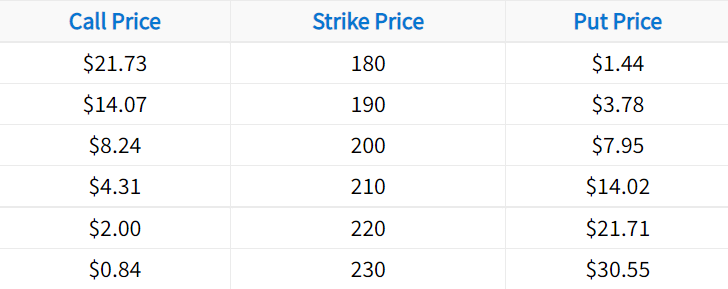

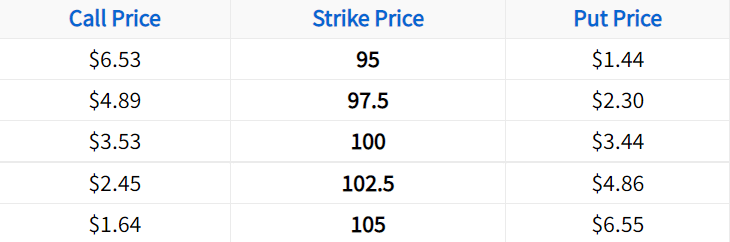

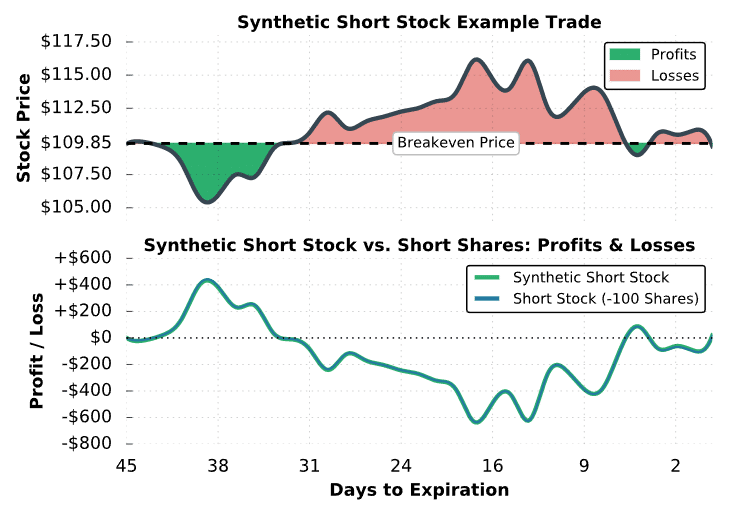

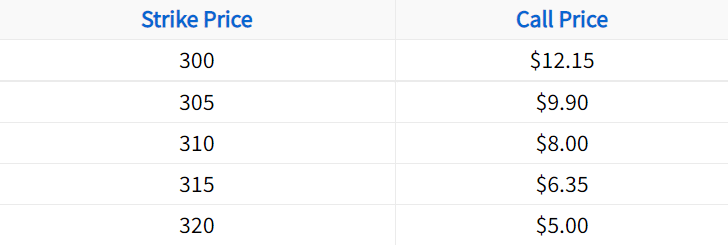

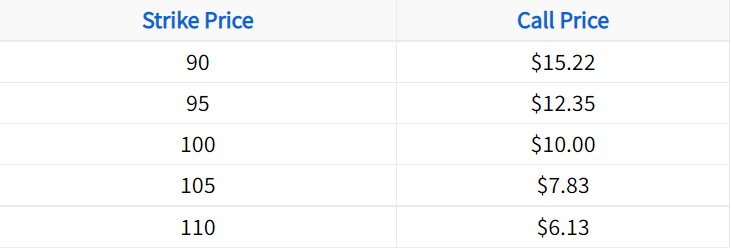

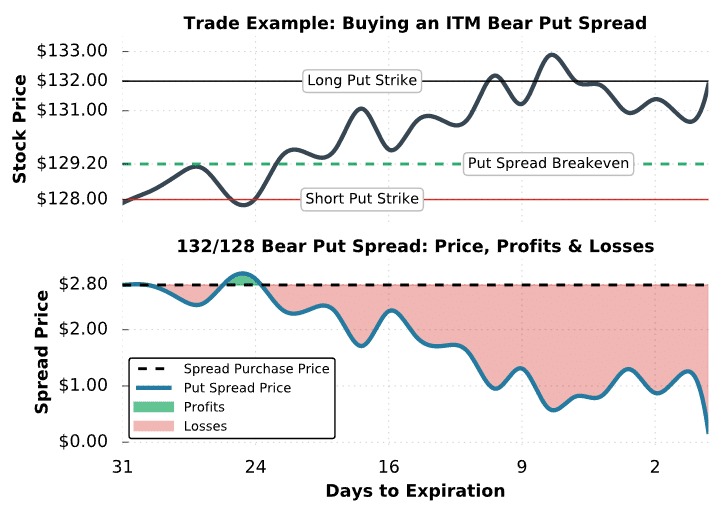

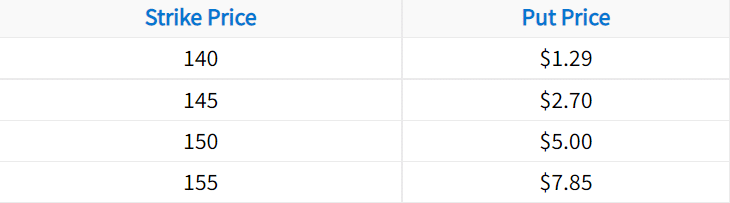

In the following example, we’ll construct a short iron condor from the following option chain:

In this case, we’ll sell the 450 put and the 550 call, and buy the 400 put and 600 call. Let’s also assume the stock price is trading for $500 when entering the position:

Initial Stock Price: $500

Short Strikes: $450 short put, $550 short call

Long Strikes: $400 long put, $600 long call

Credit Received From Short Options: $6.15 (450 put) + $7.89 (550 call) = $14.04

Debit Paid for Long Options: $0.72 (400 put) + $1.94 (600 call) = $2.66

Total Credit Received: $14.04 Credit Received – $2.66 Debit Paid = $11.38

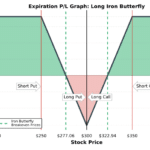

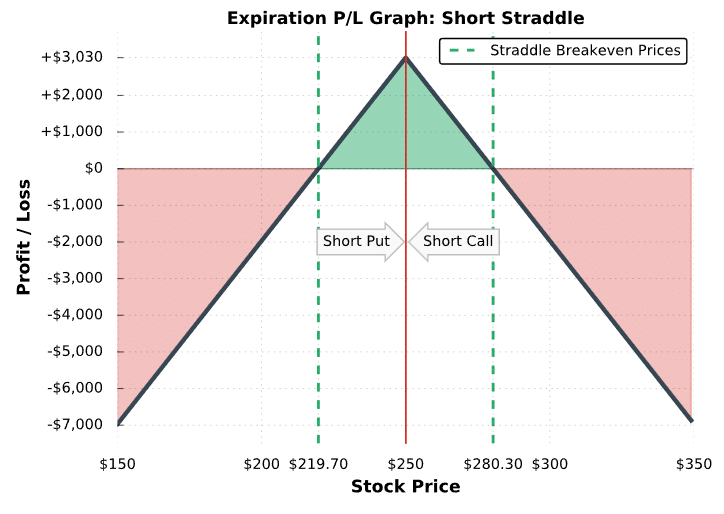

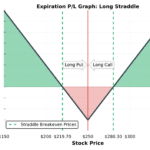

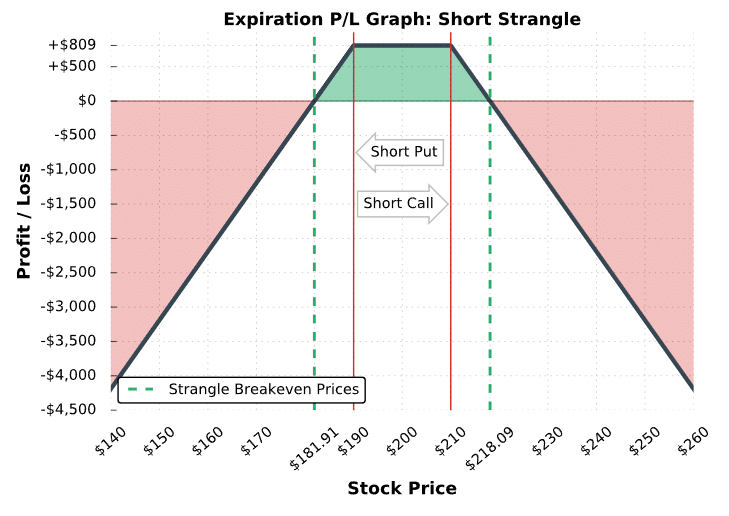

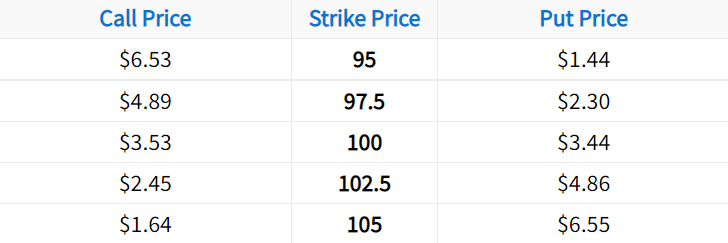

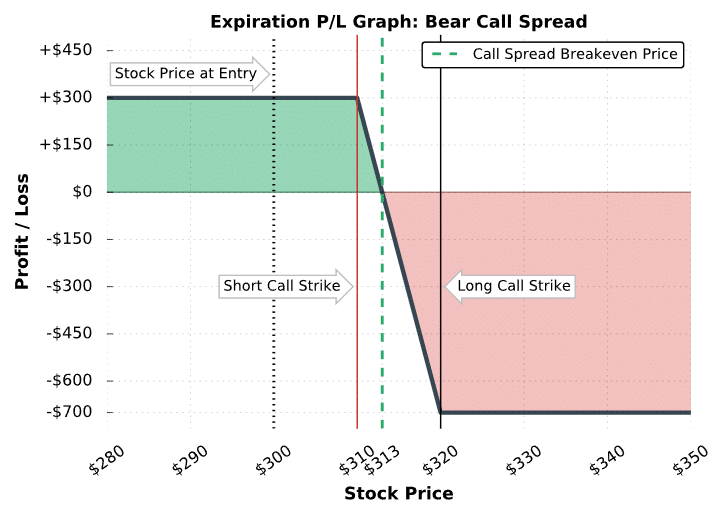

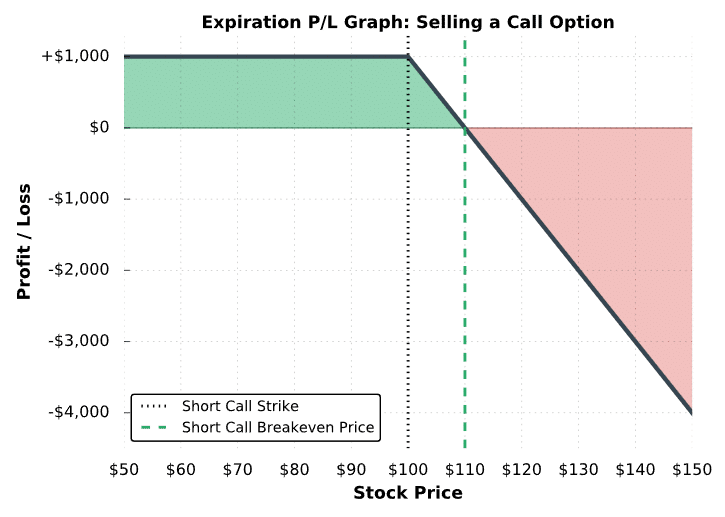

The following visual describes the potential profits and losses at expiration when selling this particular iron condor:

Iron Condor Chart

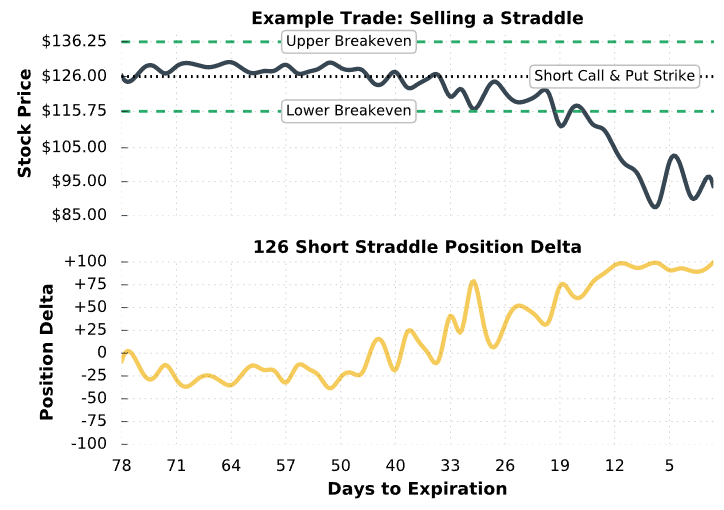

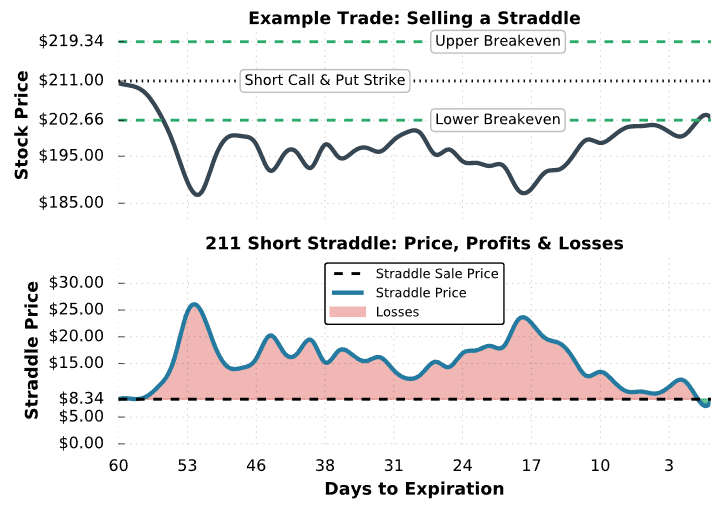

As illustrated above, the short iron condor strategy realizes its maximum profit potential when the stock price is between the short strikes at expiration, and amounts to the total credit received for selling each spread (multiplied by 100). Additionally, you’ll notice that a short iron condor has a similar risk profile to a short strangle, except the risk of a short iron condor is limited beyond the long options that are purchased.

Regarding loss potential, both the short call spread and short put spread are $50 wide. Because of this, the maximum potential loss is: ($50 strike width – $11.38 credit received) x 100 = $3,862. However, if the call spread were $100 wide (e.g. 550 short call and 650 long call), the maximum loss potential of this iron condor would be: ($100 strike width – $11.62 credit received) x 100 = $8,862. Therefore, an iron condor’s loss potential always depends on the width of the wider spread. When each spread has the same width, the risk of loss is equal on both sides.

The last thing we’ll point out about this graph is that the breakeven prices are both above and below the stock price, which means the stock can trade in a wide range and the short iron condor can be profitable. Because of this, the selling iron condors is a high probability strategy. However, this makes sense since the maximum potential loss is greater than the maximum potential reward (in general).

At this point, you know how the outcomes at expiration when selling iron condors, but what about before expiration? Understanding how profits and losses occur when selling iron condors can be explained by the position’s option Greeks.

Short Iron Condor Trade Examples

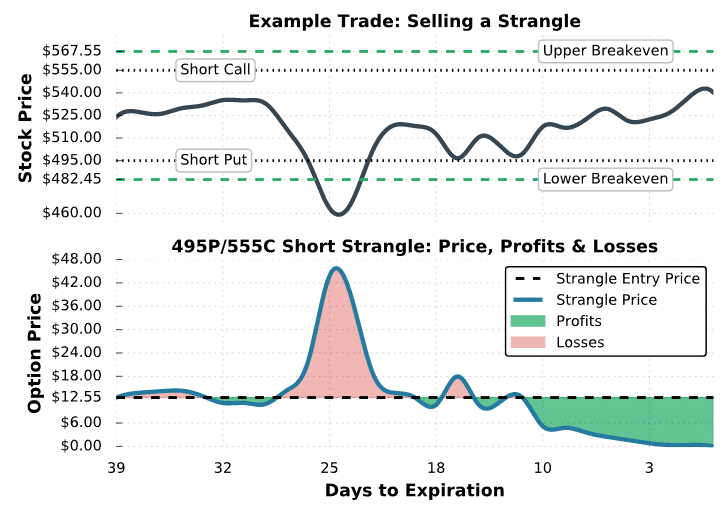

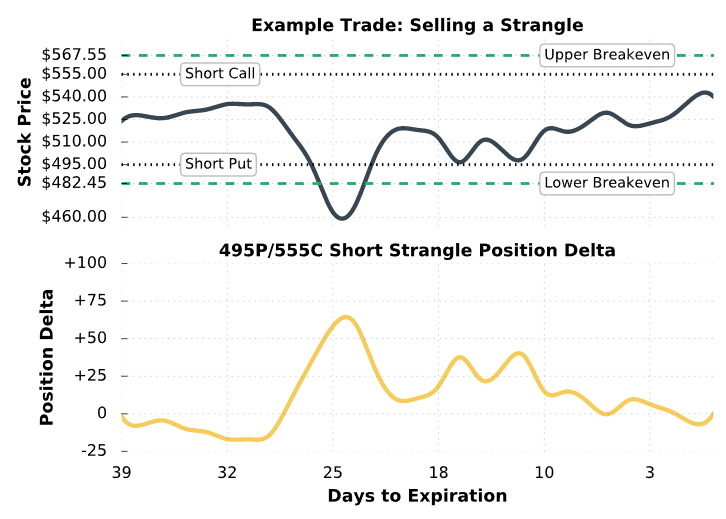

To visualize the performance of the iron condor strategy relative to the stock price, let’s look at a few examples of some iron condors that actually occurred. Note that we don’t specify the specific underlying because the concepts transfer to other stocks in the market. Additionally, each example demonstrates the performance of a single iron condor position.

When trading more contracts, the profits and losses in each case will be magnified by the number of iron condors traded.

Let’s do it!

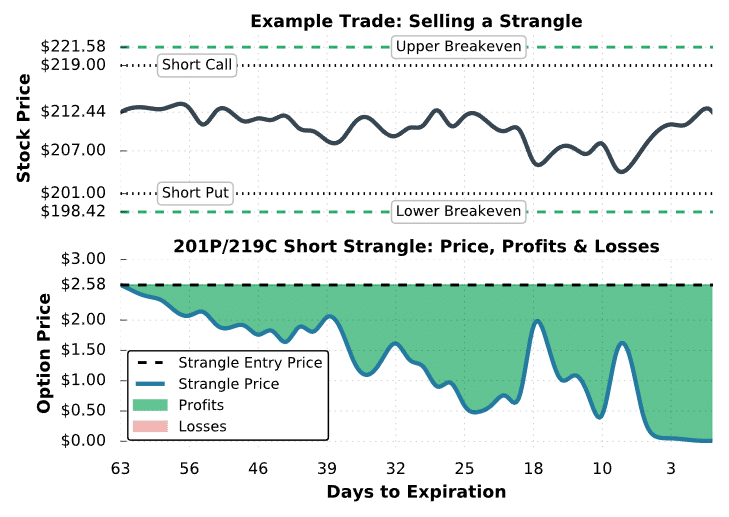

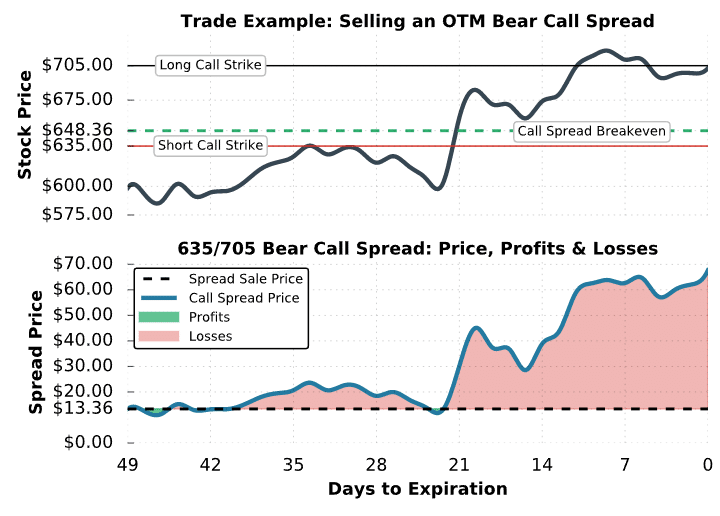

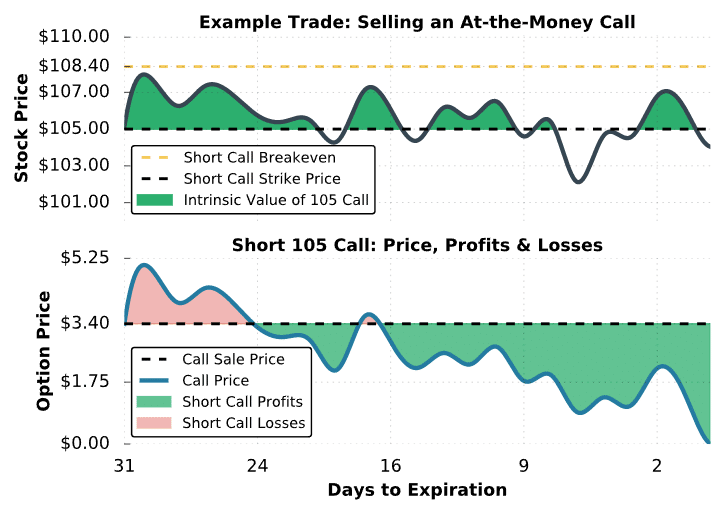

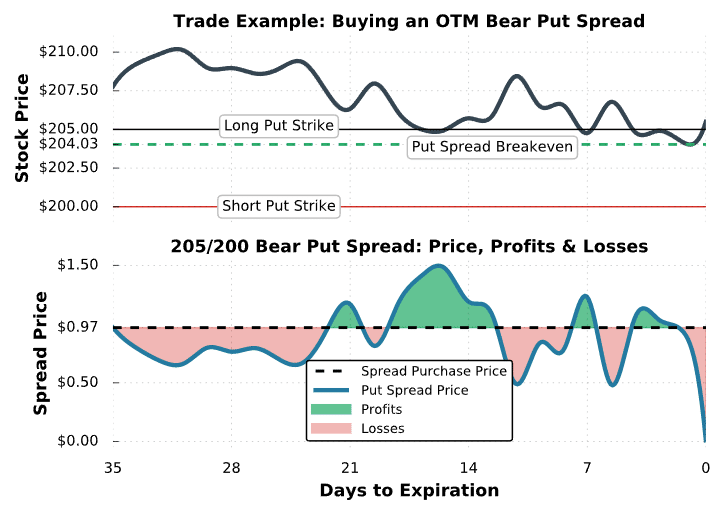

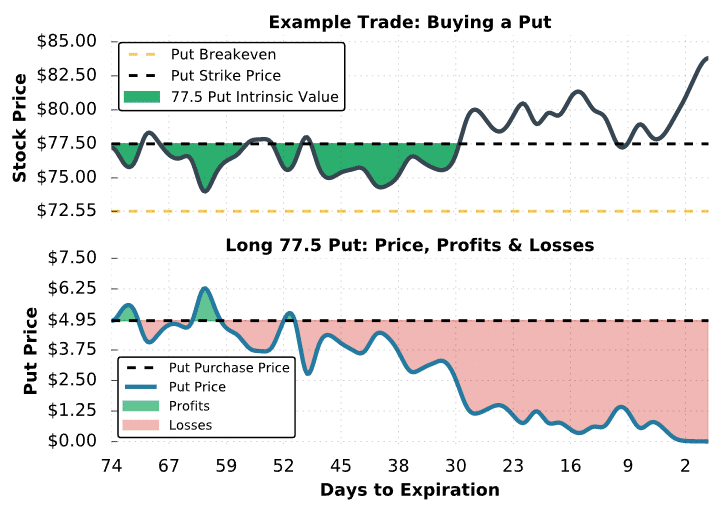

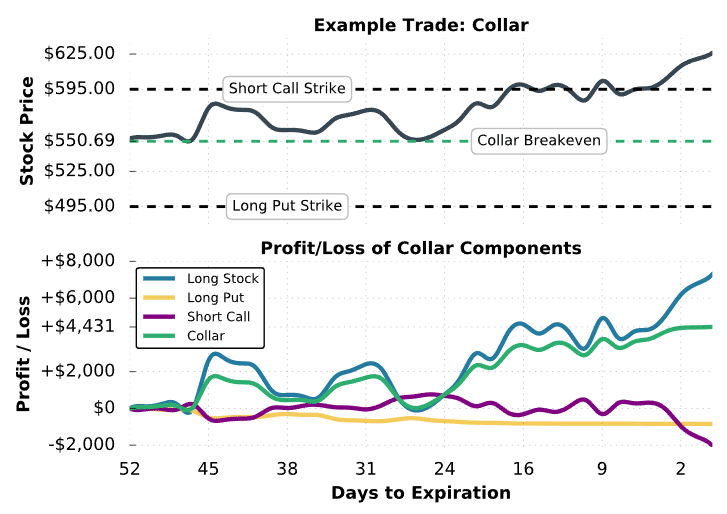

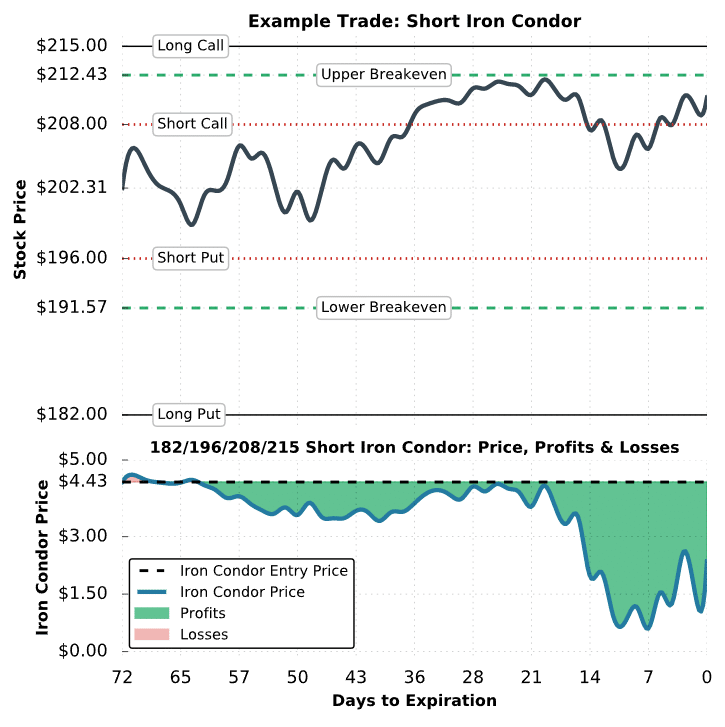

Trade Example #1: Partially Profitable Iron Condor

The first example we’ll look at is a scenario where a trader sells an iron condor, but the stock price is between the short call option and long call option at expiration. In this scenario, maximum profit will not be realized, but the strategy can still be profitable if the stock price is below the upper breakeven price.

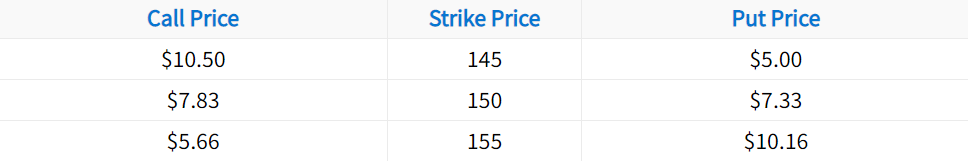

Here are the trade details:

Initial Price of The Underlying Stock: $202.31

Strikes and Expiration: Long 182 Put and 215 Call; Short 196 Put and 208 Call; All options expiring in 72 days

Net Premium Received for Short Options: $4.18 for the 196 put + $2.82 for the 208 call = $7.00 in premium collected

Net Premium Paid for Long Options: $1.79 for the 182 put + $0.78 for the 215 call = $2.57 in premium paid

Net Credit: $7.00 premium collected – $2.57 premium paid = $4.43 net credit

Breakeven Prices: $191.57 and $212.43 ($196 – $4.43 and $208 + $4.43)

Maximum Profit Potential: $4.43 net credit x 100 = $443

Maximum Loss Potential (Upside): ($7-wide call spread – $4.43 net credit) x 100 = $257

Maximum Loss Potential (Downside): ($14-wide put spread – $4.43 net credit) x 100 = $957

As mentioned earlier, the maximum loss potential of an iron condor depends on the wider spread. In this example, the short call spread is $7 wide and the short put spread is $14 wide. Because of this, the maximum loss potential of this iron condor occurs when the stock price collapses through the short put spread. More specifically, this trade has $257 in loss potential on the upside and $957 in potential losses on the downside. Consequently, this particular short iron condor position has a slightly bullish bias.

Let’s see what happens!

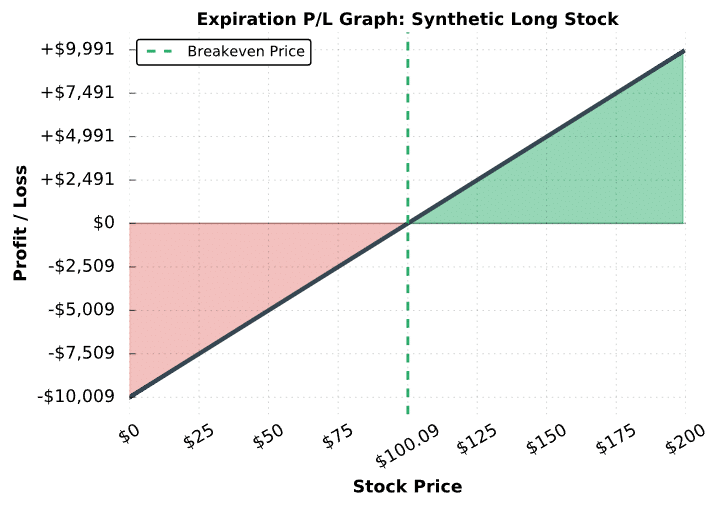

Iron Condor #1 Trade Results

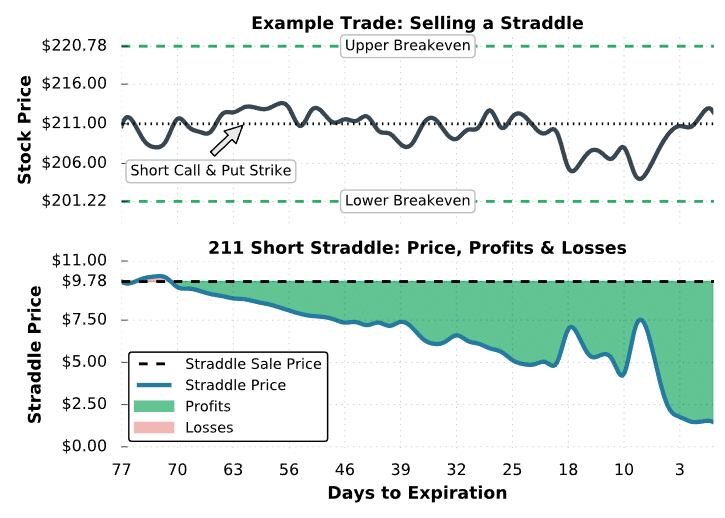

As we can see, this short iron condor position performed well because the stock price remained between the position’s breakeven points over the entire period.

With the price of the iron condor below the initial sale price nearly the entire period, the trader in this example had many opportunities to close the trade early for profits. To close an iron condor before expiration, a trader can simultaneously buy back the short options and sell the long options at their current prices.

For example, if the trader in this example closed the iron condor for $3.00, they would have locked in a profit of $143: ($4.43 initial iron condor sale price – $3.00 closing price) x 100 = +$142.

At expiration, the short 208 call was worth $2.50 because the stock price was trading for $210.50. Since all of the other options expired worthless, the final value of the iron condor is $2.50. With an initial sale price of $4.43, the profit at expiration is: ($4.43 – $2.50) x 100 = +$193.

Regarding a share assignment, this particular trader would be assigned -100 shares of stock if they did not close the in-the-money short call before expiration. If the trader did not want a short stock position, the short call would need to be bought back before expiration. However, there’s always a chance that the trader could get assigned early on the short call.

Ok, so you’ve seen a partially profitable iron condor example. Next, we’ll take a look at a scenario where a short iron condor realizes the maximum potential loss.

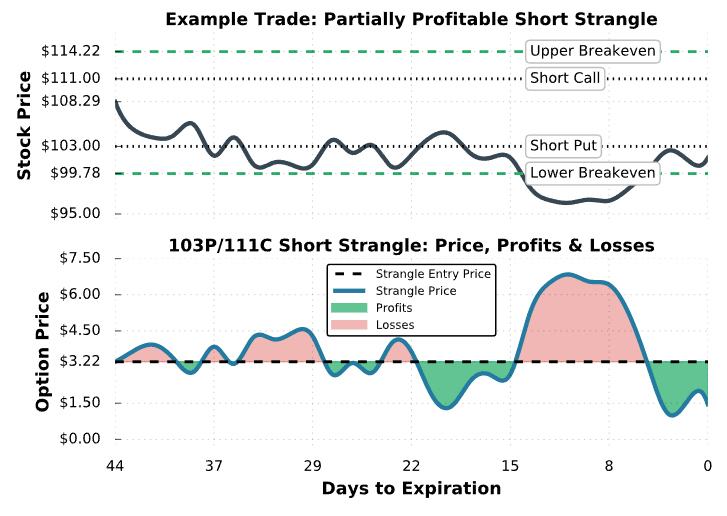

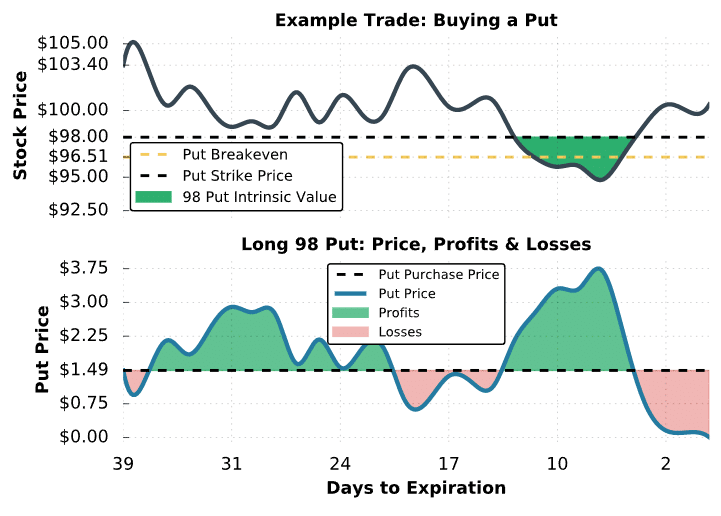

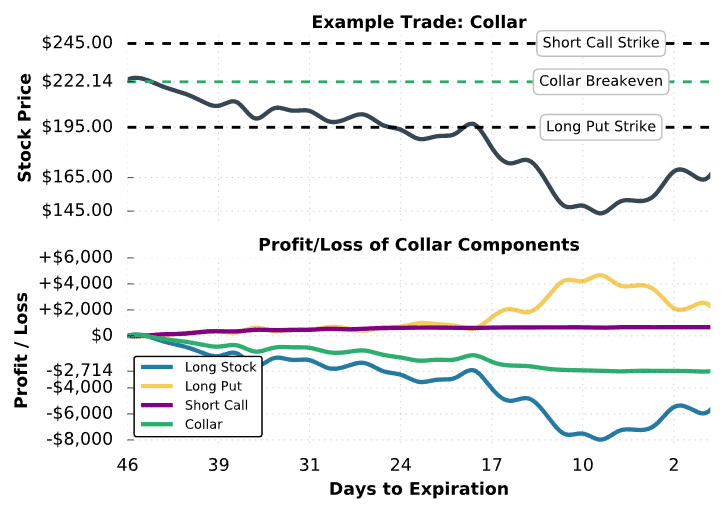

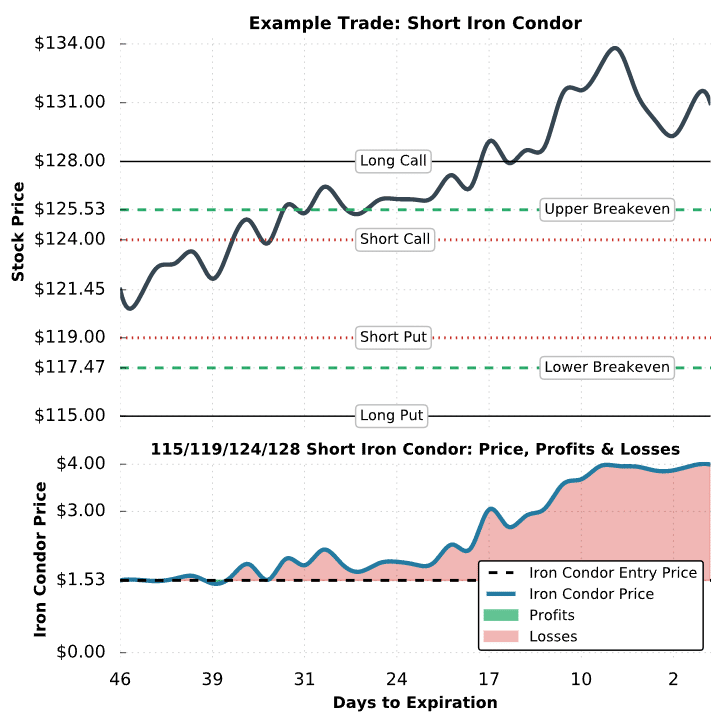

Trade Example #2: Maximum Loss Iron Condor

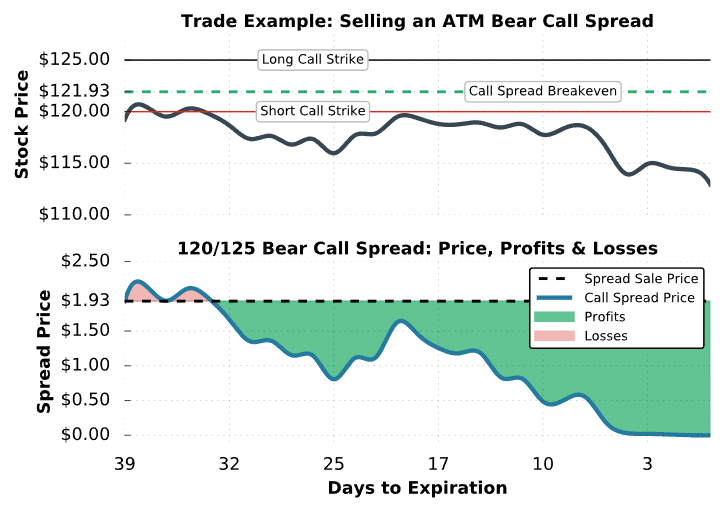

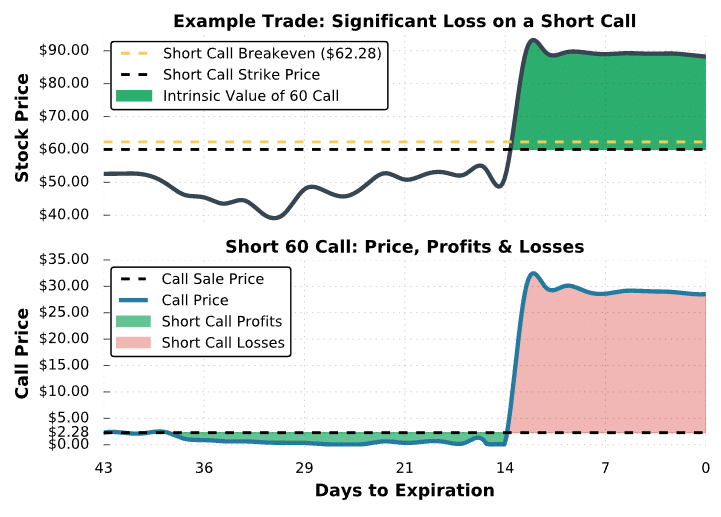

In the following example, we’ll investigate a situation where the stock price rises continuosly and is above the short call spread at expiration.

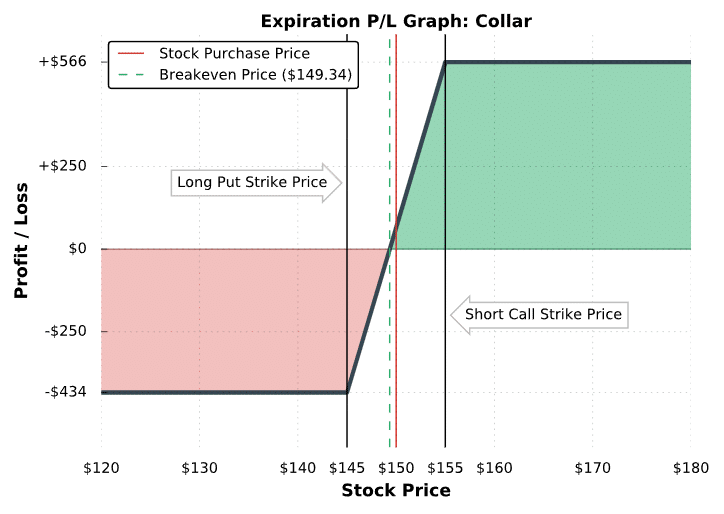

Here are the details:

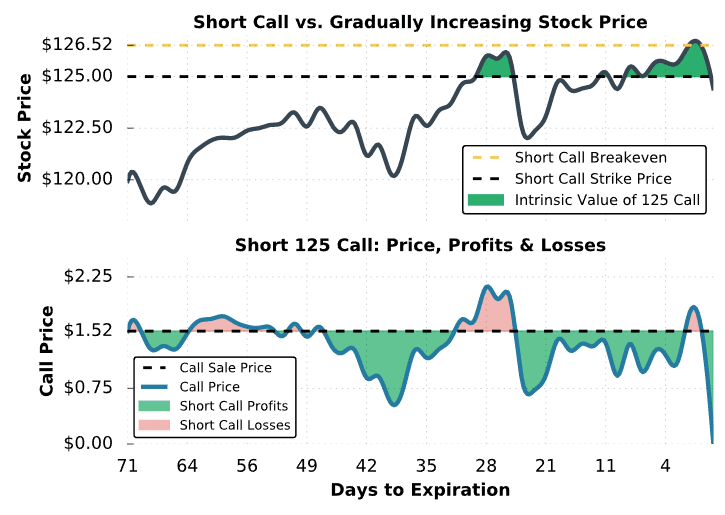

Initial Stock Price: $121.45

Strikes and Expiration: Long 115 Put and 128 Call; Short 119 Put and 124 Call; All options expiring in 46 days

Premium Collected for Short Options: $1.25 for the 119 put + $1.05 for the 124 call = $2.30 in premium collected

Premium Paid for Long Options: $0.39 for the 115 put + $0.38 for the 128 call = $0.77 in premium paid

Net Credit: $2.30 premium collected – $0.77 premium paid = $1.53 net credit

Breakeven Prices: $117.47 and $125.53 ($119 – $1.53 and $124 + $1.53)

Maximum Profit Potential: $1.53 net credit x 100 = $153

Maximum Risk: ($4-wide spreads – $1.53 net credit) x 100 = $247

In this example, both the short call spread and short put spread are $4 wide, so the risk is equal on both sides of the trade.

Let’s take a look at the trade’s performance:

Iron Condor #2 Trade Results

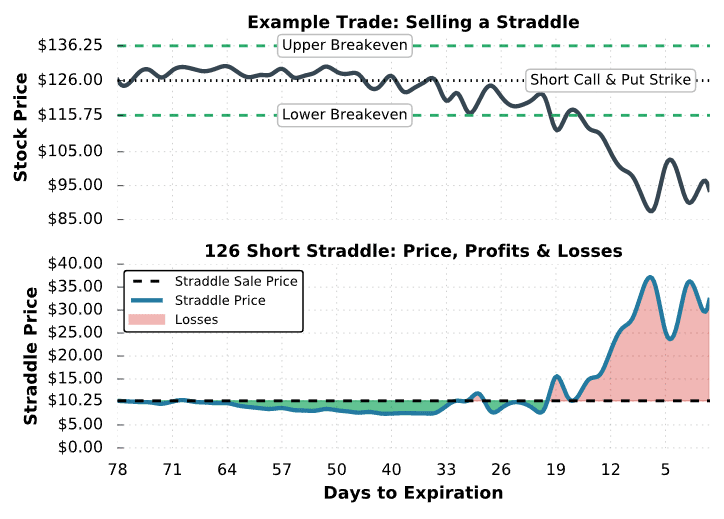

As we can see in this example, the stock price rallied from $121 to over $130 during the duration of this trade. Since the stock price increased steadily after entering the trade, the position suffered losses and was never profitable.

At expiration, the stock price was above $128, which means the short 124/128 call spread was entirely in-the-money (ITM) and was therefore worth $4, which is the width of the spread.

On the other hand, the short 119/115 put spread expired worthless because both put options were out-of-the-money (OTM).

With the iron condor being worth $4 at expiration, the trader’s loss in this example is $247 per iron condor, as the position was sold for $1.53 but ended at $4.00.

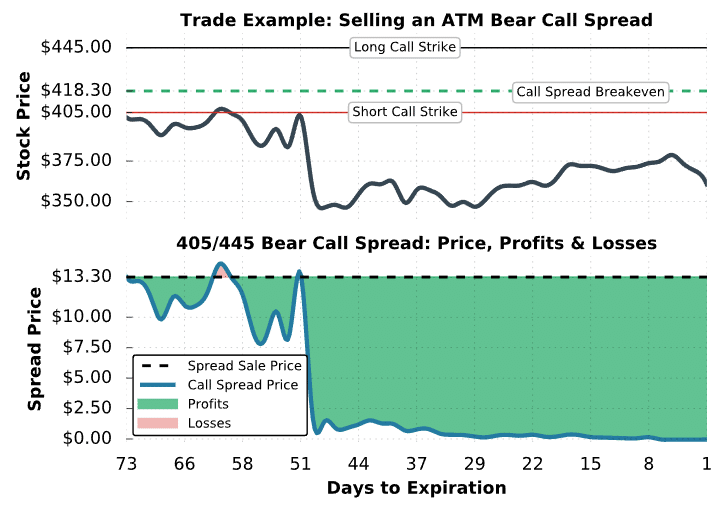

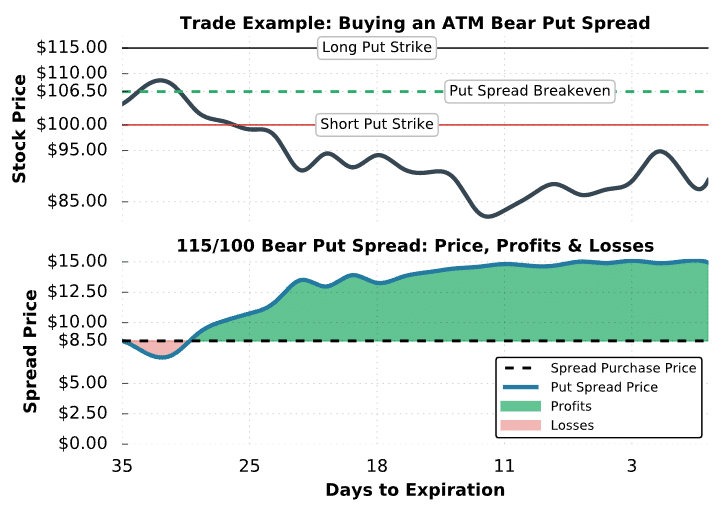

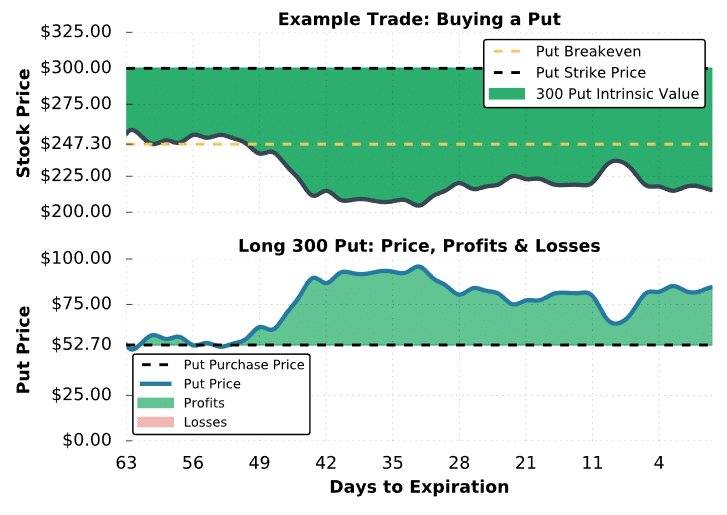

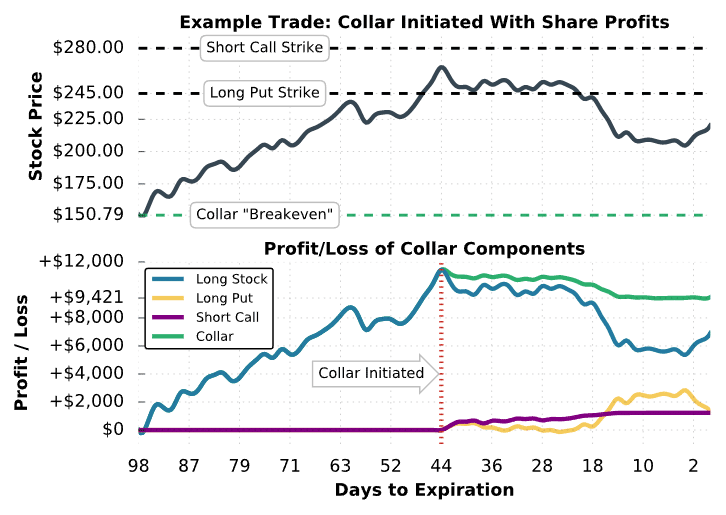

Trade Example #3: Max Profit Iron Condor

In the final example, we’ll look at a scenario where a short iron condor trader only makes full profit at expiration. The maximum profit of an iron condor occurs when the stock price is between the short strikes at expiration.

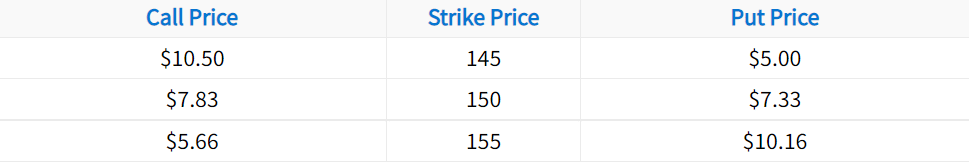

Here are the trade details:

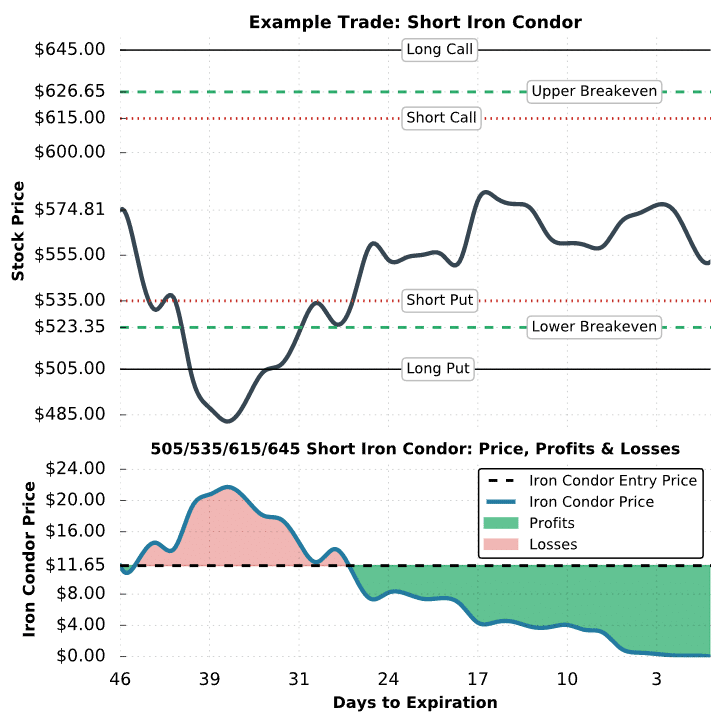

Initial Stock Price: $574.81

Strikes and Expiration: Long 505 Put and 645 Call; Short 535 Put and 615 Call; All options expiring in 46 days

Premium Collected for Short Options: $11.75 for the 535 put + $10.40 for the 615 call = $22.15 in premium collected

Premium Paid for Long Options: $6.03 for the 505 put + $4.47 for the 645 call = $10.50 in premium paid

Net Credit: $22.15 premium collected – $10.50 premium paid = $11.65 net credit

Breakeven Prices: $523.35 and $626.65 ($535 – $11.65 and $615 + $11.65)

Maximum Profit Potential: $11.65 net credit x 100 = $1,165

Maximum Loss Potential: ($30-wide spreads – $11.65 net credit) x 100 = $1,835

Let’s see this historical trade’s performance!

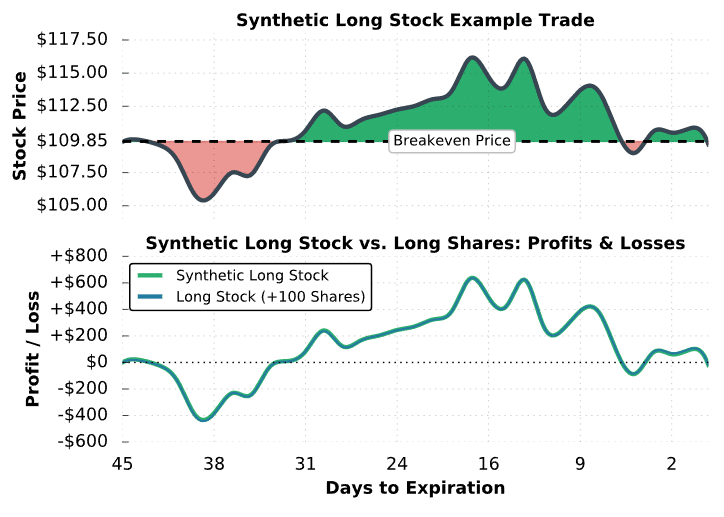

Iron Condor #3 Trade Results

In this case, the stock price collapsed immediately after the iron condor was sold. As a result, the iron condor price jumped from $11.65 to over $20.00, which translated to a loss of over $850 for the iron condor seller. Fortunately, the stock price rallied back between the position’s short strikes and the position decayed as expiration approached.

Finally, at expiration, all of the options expired worthless since the stock price was between the short strikes of each spread. With an initial sale price of $11.65, the profit on this trade is $1,165: ($11.65 sale price – $0 expiration price) x 100 = +$1,165.

Final Word

Let’s review what we have learned:

- An iron condor consists of selling both a put spread (long put/short put) and a call spread (long call/short call) simultaneously

- Both of these spreads must be of the same width and expiration

- Iron condor’s profit when the options sold decrease in value

- Short iron condors are best suited for market-neutral traders

- Most iron condors have a greater than 50% chance of success

- Maximum loss is greater than maximum profit for most iron condors

- A high volatility environment allows traders to collect more premium from iron condors sold

- Iron condors with 30-60 days to expiration are ideal as this time frame allows traders to profit from time decay, or the Greek “theta”

Options trading involves risks. To learn more about these risks, please read the risks of standardized options from The OCC.

Short Iron Condor FAQs

The long iron condor is the exact opposite trade of the short iron condor. Long iron condors are purchased for a debit while short iron condors are sold for a net credit.

When you buy an iron condor, you believe the underlying stock will make a large directional move either up or down. Short iron condors profit in a neutral market.

Short iron condors can go into expiration as long as both the short call option and short put option are safely out-of-the-money. If either of these legs is close to being in-the-money as expiration nears, it is best practice to trade out of these options.

Next Lesson

-

Bear Call Spread Explained

January 28, 2022 -

Bull Put Spread Explained

January 28, 2022 -

3 Best Credit Spread Strategies

January 24, 2022 -

Long Iron Condor Explained – The Ultimate Guide

January 31, 2022 -

Iron Condor Options Strategy (Tutorial + Trade Examples)

February 1, 2022 -

Selling Straddles on SPY

February 2, 2022

Additional Resources