Last updated on March 3rd, 2022 , 07:14 am

Marker Order Definition: A market order is an order to buy or sell a security at the immediate and best available price. Fill price is unknown in market orders.

Market orders are the enemy of all options traders. Why? Because you have no idea the price at which you will get filled.

In the above definition, we can see that market orders are filled at the immediate and best price. However, due to the notorious illiquidity of call and put options, that “best” price can be very poor indeed.

Let’s find out why!

Jump To

TAKEAWAYS

- Market orders guarantee a trade will get filled, but the price at which that trade will be filled is unknown.

- Stop-loss orders are simply market orders waiting to get triggered.

- An options volume tells us how many contracts have traded all day; an options open interest tells us how many options are in existence.

- The bid-ask spread of an option is the difference between its bid price and ask price.

- The above two components of liquidity are vital for getting decent fills. Market orders in options with poor liquidity can result in horrible fill prices.

- Limit orders are the best alternative to market orders.

Market Order in Options Explained

Whenever you place a trade, the order form on your trading software will require some basic information about the trade:

1.) The security you wish to trade.

2.) Whether or not you want to buy or sell that security.

3.) The time and duration you want that order working for (Time In Force “TIF”).

4.) The actual order type.

This article is concerned with the latter on the above list, order types.

When trading options or stocks (or any security) you must instruct your broker of the type of order you want to place.

Let’s explore the different order types next!

New to options trading? Learn the essential concepts of options trading with our FREE 160+ page Options Trading for Beginners PDF.

Order Types in Options Trading

Order types include, but are not limited to:

The “limit” order type tells your broker you want to get filled at or better than your set limit price.

The “stop-loss” order is triggered when the set stop price is breached. The order then becomes a market order.

The “stop-limit” order is triggered when the stop price is reached. However, unlike the stop-loss order, the stop-limit order triggers a limit order.

The “trailing-stop order” allows a trader to set an upper bound or loss percentage on a trade. This allows a trader to lock in profits or losses in connection with the securities movement.

A market order instructs the broker a customer wants to get filled immediately, regardless of price.

As we can see above, the stop-loss order is essentially a market order in disguise. Your broker holds stop-loss orders until the price is breached, and then sends the order to market makers. These order types are not visible until they get triggered.

So why are market orders a bad idea? It’s all about liquidity!

Market Orders In Options and Liquidity

When you’re trading stocks, liquidity is generally not a problem. This is assuming, of course, you’re not trading exotic penny stocks.

Most stocks have spreads a couple of pennies wide. This means if you want to turn around and sell a stock the moment after you buy it, you will only lose a few pennies.

With options, liquidity is not so plentiful.

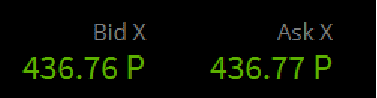

Let’s take AAPL stock for example. Currently, you can buy AAPL for 436.77 and immediately sell it for 436.76. Here’s how that looks on the tastyworks software:

So why is there such great liquidity in AAPL stock? Because there is only one tradable equity! What you can’t see is the order size; there are about 10k shares of stock bid at 436.76 and 11k shares offered at 436.77. Using a market order probably won’t harm you here.

But there are thousands of options that trade on AAPL. Every one of these options requires its own market. Since there aren’t as many players, that spread can widen out considerably.

This can lead to wide markets and low volume/open interest. This is bad news for market orders! Let’s examine both of these next, as they are the crucial components of options trading liquidity.

Volume and Open Interest in Options Trading

The first two components of option liquidity are open interest and volume.

Option Open Interest: The open interest of a particular option refers to how many contracts are currently in existence. The higher the open interest, the greater the liquidity.

Option Volume: The volume of an option refers to how many contracts have been traded on a specific day.

Bid-Ask Spread in Options Trading

The next component of the liquidity of an option is the bid-ask spread.

Option Bid-Ask Spread: The difference between the bid price and the ask price.

This market essentially tells us what we can buy an option for, then immediately sell it for. If markets are wide, you’re going to start off with a huge loss right off the bat!

Additionally, you want to make sure the bid and ask size is appropriate. Sometimes, there is only one option bid at a certain price. If you are trying to sell more than one option, the next bid may be a dollar or more below the current bid!

These are known as thin markets. The bid-ask spread can be deceiving!

Let’s take a look at a couple of examples now.

Option Liquidity Example: High Liquidity

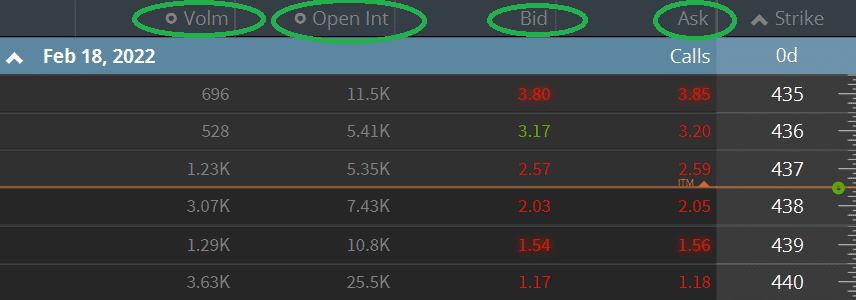

The below image is taken from the tastyworks software. It shows the volume/open interest and bid-ask spreads for call options on SPY options. SPY (an S&P 500 tracking ETF) is the most liquid ETF in the world.

SPY Call Options

The volume and open interest for these ETF options are mostly in the thousands. Additionally, the bid-ask spread is only a few pennies wide.

If you use a market order (or stop-loss) on these options, you’ll probably be OK.

But still – why risk it? Use a limit order!

Option Liquidity Example: Low Liquidity

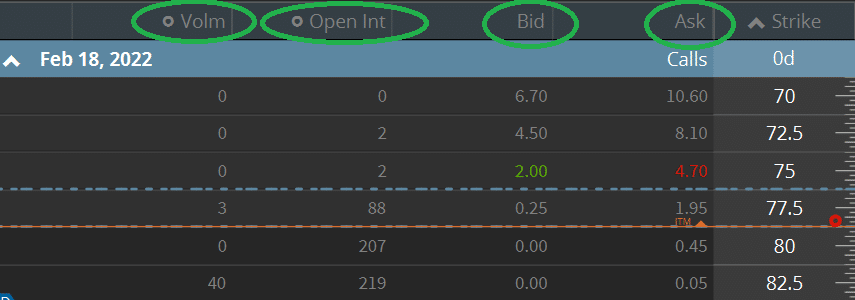

The below image (taken from the tastyworks software) shows the option markets on a few call options for stock symbol R (Ryder Systems).

The above options are incredibly illiquid. Never trade options like these. The volume is almost non-existent. The open interest is shameful. And you can park a truck between the bid-ask spread.

What you can’t see is the size of these markets. Guess what? The size is as thin as paper on a lot of these options.

Placing a market order on these options may cost you an arm and a leg.

The solution? Don’t trade this security! If you must, use a limit order, and work that limit order up in nickel increments until you get filled.

Final Word: Market Orders on Options

I have personally never used a market order to enter or exit an options trade.

I have, however, used market orders under the instructions of advisors. I have sold options for 0.10 only to see them bid at 0.75 a minute later.

In particular, stop-loss orders on the open can result in abysmal fills.

At the end of the day, just use limit orders. It’s that simple. If you can’t be around to monitor your trades, don’t trade

FAQs: Market Orders on Options

If you’re trading liquid products, market orders can be relatively safe. When you’re trading illiquid products (or trading around the open/close) market orders pose significant risks.

Market orders are filled at any price immediately; limit orders are filled when the security trades at the limit price. Limit orders are not always filled.

The “market” order type communicates to your broker you want to get filled immediately, regardless of execution price.

Market orders with the “Day” TIF designation get filled immediately. Market orders with the “EXT” designation get filled immediately in the extended hours market.

If you place a market order and the market is open, you will get filled immediately. Therefore, expiration does not apply to market orders.